Having someone at home with Alzheimer's or dementia can be challenging, but can also be rewarding. In the early stages of dementia things are pretty normal and life carries on pretty much as always. As time goes on and the disease progresses, changes have to be made both to the physical environment and also in day to day life.

There are many different types of dementia and each situation and person is different, but research has shown some common techniques that work well to help the person maintain their abilities as long as possible and lead a fulfilling life.

HABITS AND ROUTINES FOR DEMENTIA CARE

One of the most important concepts is to realize that the more things can stay the same, the better it is. Habits and routines that have developed over time play a strong role in helping the person with de mentia cope with life. Change is hard enough to deal with for healthy people, it is that much harder for someone with dementia. Obviously some changes have to be made, but keeping things as close to the way they were is most beneficial.

Reinforcing existing routines and creating new ones in the early stages of dementia will help the person as the disease progresses and their abilities decline. Research has shown that the type of memory where habits are stored (procedural memory) is spared in dementia. In other words, they will retain those skills longer.

An example of this is to have a designated container in a central place for the person with alzheimer s to put their keys, their wallet, other personal items that commonly go missing. Encourage the person to get into the habit of always putting their things into this container. By establishing this routine they will always know where to look for them, and when they become concerned that they are missing they will look in the container. If they don't, you can suggest it.

It is important to keep the person engaged and participating in helping around the house. This helps them feel important and needed. Be sure to give them roles that are within their abilities, such things as clearing the table, leading grace or feeding the cat. Help them be successful, but let them do the job. Adjust their roles as their abilities change and the dementia progresses, but try to keep them doing the same things even if it is in a different way.

Having a set structure to the flow of each day is another way to support the person. It adds predictability. The days become a habit in themselves. The person becomes used to eating at noon, then feeding the cat and then having a nap. Because of the routine, one activity will prompt the next. Try to establish as much of a pattern to each day as possible. Obviously one day cannot necessarily be structured exactly the same as the next, but keeping them as consistent as possible is the goal.

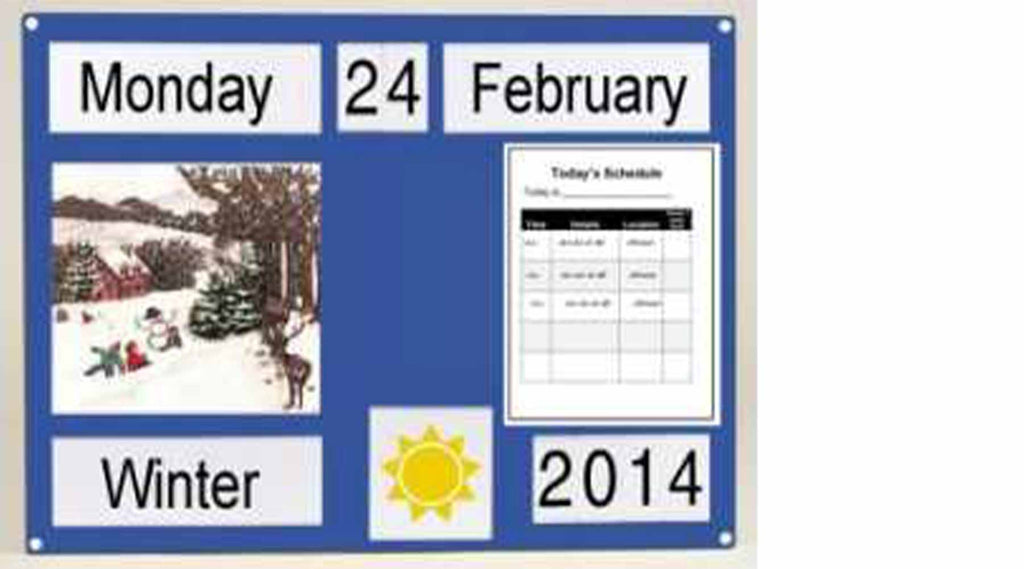

In order to help the person know what's happening for the day it is a good idea to get into the practice of creating a dementia specific schedule. This should be easy to read and list the times and location (if appropriate) for each activity planned for the day. Leave a spot to check off items that have been completed to make it easy to follow.

This schedule should be place in a central location with a whiteboard or bulletin board that becomes the information center. All the important information should be available here. In addition to the schedule, the board should show the day of the week, upcoming events, the weather, anything of interest or importance. The information should be clearly displayed, easy to read and not cluttered. When the person asks you what day it is, help them to answer it themselves by encouraging them to look at the board. This will help create the habit of always going to the board for information which they will continue to do as the dementia progresses.

HOBBIES

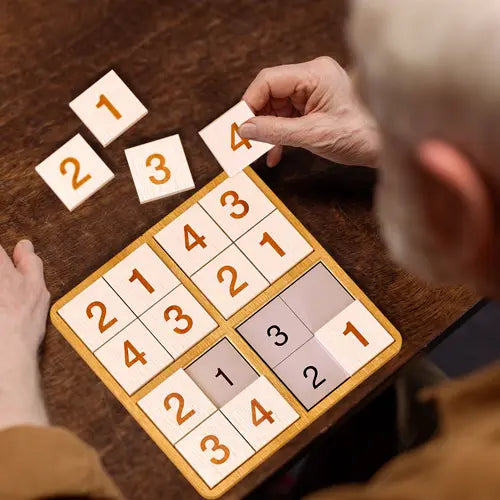

Early in the disease the person may appear to lose interest in activities that they used to enjoy. Maybe they used to do crossword puzzles but now you never see them working on one. Maybe they used to always have a jigsaw puzzle on the go, but now it goes untouched. This doesn't necessarily mean that they have lost interest. It most likely is an indication that their recent experiences with the activity have been ones of frustration and failure. Instead of the activity being associated with a feeling of success and pleasure, it is now associated with negative feelings and that is why they avoid it.

Don't ignore this. Instead work towards re-establishing the positive feelings by helping them to be successful at the activity. Maybe you could start a crossword and then ask them for help, only asking them questions that you are sure they can answer correctly. If they don't come up with the answer quickly, don't let them stew over it. Immediately offer them two choices and ask them which they think is correct. Another option is to use a crossword puzzle designed for dementia and Alzheimer's patients such as our Simple Crossword Puzzle.

You could start working on a jigsaw puzzle that has been designed to facilitate success. Ask the person to help you find the border pieces, or maybe find the pieces of a particular flower. Something distinctive and easy to recognize. Congratulate them on their successes and share in the joy. These methods will help them reestablish positive feelings when they see the activity. Not only does this allow them to do something that gives them pleasure, it also allows you to build on this pleasure with other, similar activities.

An even better solution is to be aware of the problem before it becomes entrenched. If you see the person struggling and showing signs of frustration while working on something they love to do, step in and figure out what the problem is. Help them to finish the activity successfully, but let them finish it. Give them clues, offer choices for them to pick from, offer them the piece of the puzzle they are looking for and ask them if they think that might work. Congratulate them for doing well.

It is a good idea to introduce the person to new "hobbies" early in the dementia so that they will be well established as their abilities change. These should be activities that they can do on their own with little direction. They should be within their current ability and scalable to suit them as the dementia progresses. For example, perhaps they could clip coupons and save them for appropriate family members. Maybe they would enjoy keeping a book recording something, maybe the weather, maybe the phase of the moon.