If a person with dementia and Alzheimer's disease that you are caring for asks "Where's Henry?", referring to their spouse who passed away several years ago, how do you respond? Do you tell them that Henry passed away three years ago? Do you ignore the question and start talking about something else? Or do you lie and say that Henry is away for a while?

Telling them the simple truth is quick and easy (at least in the short term), but may not be the best approach. It may result in the person having bad feelings, perhaps even becoming distraught, and it could happen over and over again.

So how do we know?

There are no official guidelines from governing dementia care organizations about the use of therapeutic lying, nor has much research been done on the practice. One study in the UK found that 98% of nurses admitted telling therapeutic lies to dementia patients, as did two-thirds of psychiatrists. Ian James, a consultant clinical psychologist in the UK says "The skill of the nurse is to know when to use a therapeutic lie and to know why it is needed, but the best thing to do is to distract the patient so the nurse does not get drawn into the ethical issue of telling a lie."

Other common questions:

Where are my children?

Often the person is asking about their children because they lack a sense of purpose. In thinking about their children, they think about the responsibility that they had in caring for them. If this is the case, offering the person chores to do during the day such as folding the laundry, setting the table or doing dishes can give them back the sense of purpose.

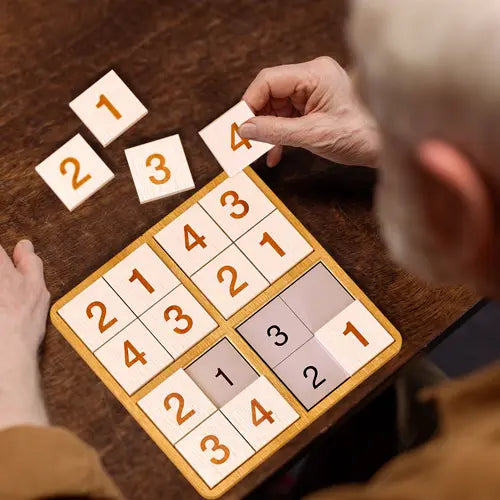

In our Montessori dementia care DementiAbility training, we call these tasks "roles" and they play an important part in improving quality of life. The person feels that the task they are doing is their contribution to the smooth running of the household which gives them a purpose, generating a sense of accomplishment, of contributing. It becomes their role, their specialty, what they are known for and others can show their appreciation for a job well done.

When can I go home?

This is a common question in care facilities usually asked in the late afternoon. When a woman who raised a family asks this question, it is often because she feels that she should be home preparing supper and doing other chores for her family.

A good way to help the person may be to involve her in a chore-style task that is reminiscent of her late afternoon routine at home - peeling a potato, wiping the tables or washing the dishes from a bake group, for example. Making this part of her daily routine, before she has the feeling that she should be "home" will improve her quality of life and may prevent the question from ever being asked.

Often when a person with dementia asks a question, it is not that they need an answer to the specific question asked, but rather that they are missing or craving something that the question represents. We need to try to understand why the person is asking that particular question, and what meaning there may be behind it. In the example above they may be asking about their spouse because they are missing having the feeling of being loved, of belonging, of security and of friendship.

Rather than answer the question directly, a better response might be to distract the person from the question by trying to help them resolve those issues. You could talk about other family members - "I saw your daughter was in this afternoon for a visit, she looks so much like you. I heard the two of your singing You Are My Sunshine - that song always makes me smile" and then start singing the song.

In doing this, you are encouraging the person to re-live a positive experience with family and by encouraging her to sing, it changes the focus to something else. After singing, you might ask for her help to do some task which will engage her and keep her from thinking about her husband.

Sometimes the question asked may be more personal and the response may require a little more thought. For example, a person may say that she and her friend (who passed away many years ago) are going out to a dance that evening.

You could simply tell her that her friend passed away and that they won't be going dancing. While certainly true, that response serves no purpose and will likely lead to feelings of grief and distress, as if the death just happened.

A better approach may be to acknowledge that she misses having outings with her friends and tell her that there are dance lessons just starting up and ask if she would like to sign up for them.

You might instead tell her that you saw her dancing at the last music event and remember how she seemed to really enjoy it. You can ask her what it was like to go out to the dances with her friends.

Or, you could tell her that her friend said that she won't be able to make it and why don't the two of you go for a walk instead. In other words, lie.

Therapeutic Lying

Most of us are raised from a young age to tell the truth and we have no desire to lie, especially to someone in our care. In almost all cases, if you're going to give an answer, telling the truth is best. There are times, however, when telling a simple lie that has no consequence may comfort the person and cause no harm. These are known as "therapeutic lies". They can be an effective way to ease a situation but must be used with care and caution.

Therapeutic lies can be thought of as lies with a positive outcome, lies that have little or no consequence. They are best used to help get through a brief moment of confusion. A common example might be to tell someone that you have made them a milkshake to encourage them to enjoy their meal replacement drink. Even though it is technically a lie, there are only good consequences and no harm is done.

The more common type of therapeutic lies are lies of omission. If a person refers to an airplane as a helicopter, for example, what difference does it make? What is there to be gained by correcting them? If the person talks about President Kennedy as if he is the current president, why correct them? It really doesn't matter and you avoid the potential of making the person feel bad because they were wrong. Lies of omission are the least contentious type of therapeutic lying and generally have no lasting consequences.

Under no circumstances should therapeutic lying be used to make the life of the caregiver easier, nor should it be used to create a false reality for the person. If used improperly, therapeutic lying can cause distrust and can be demeaning to the person. If the person realizes that they’ve been deceived, they feel like they've been taken for a fool which lowers their self-esteem. They will be less likely to trust you and that will make your role as caregiver that much more difficult. Other caregivers may joke about the deception lowering their respect for the person, and affecting the care that they give.

Some examples of lying that would not be considered "therapeutic":

Example One

A resident in a facility was insistent on catching a bus and kept asking staff where he could find the bus stop. In order to get him to stop asking, a caregiver told him that the bus stop was just outside the door and that he should sit in the chair to wait for it.

In this case the purpose of the lie was to make the caregiver's day easier, not to further the care of the resident. This is not an example of therapeutic lying, it is an example of poor care. A better approach would have been to try to determine why the person needed to catch a bus and deal with the underlying problem rather than lie to them.

Example Two

A person wants to wear the same sweater every day because it's their favorite, but you want them to wear something else so you take the sweater away. When the person says that she can't find her sweater and asks where it is, you lie and tell her that it's in the laundry.

The likely outcome of this situation is that the woman will continue to search high and low for her favorite sweater, getting more and more distraught. The real issue here is, why can't the woman wear her favorite sweater every day? When it needs laundering, you can truthfully tell her that the sweater needs to get cleaned and get it back to her as soon as possible.

Example Three

A resident was always searching for someone and was constantly on his feet walking around looking for the person. He walked so much that he actually lost weight and wouldn’t stop to eat or drink. A caregiver who knew that the resident used to be in the army told him one day that there was a call for him from "the colonel" and that he should wait in the dining room for the call.

While he was waiting, he ate the food placed on the table in front of him.

The lie helped him as it enabled him to eat and drink, which of course was of benefit to the resident. But what happens when the call doesn't come? What happens when someone else asks "what colonel?". This lie may be therapeutic if everyone involved is aware of the lie and plays along but it is still fraught with potential problems. What happens the next time it's time to eat - does the resident remember that the call never came? Does he feel demeaned and cheated because of it?

It is most important that whatever method we choose, the feelings and well-being of the person with dementia should be paramount. As Tony McElveen, ST5 Old Age Psychiatry, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde says:

“ Yet if the function of truth in a situation is to bring nothing but pain and distress to a confused, demented fellow human being, then its utilisation in that instance is at best futile, at worst cruel. When we have exhausted all other possible therapeutic options – including truth-telling – and only when it is likely to enhance the person's well- being, should a ‘best interests lie’ be trialed and the benefit reassessed."