This is one in a series of posts describing the ten Montessori Principles for dementia care. Click here for the first post in the series

What exactly do we mean by “independence”? We aren’t talking about the person with dementia living by themselves, nor even necessarily doing many of life’s daily chores on their own. We are talking about the person being given the opportunity to do as much as they are capable of doing.

People with Alzheimer's or dementia gradually lose their ability to remember orienting information which makes it difficult for them to do many simple tasks. They can’t find their wallet, they struggle with what to wear and with getting dressed, for example. The easy answer is to start doing these things for the dementia patients because it’s faster and simpler. That is the loss of independence that we’re talking about.

There are two consequences to taking over these tasks. First, the person loses some of their engagement in life. They withdraw because their input is no longer necessary – decisions and actions are being made for them. Second, they may lose the ability to do some things through lack of doing it. For example, if the person takes a long time doing up their buttons, someone may do it for them. Because they are no longer doing the activity, they may no longer be able to recall the steps involved and may lose the ability altogether. Our article on “excess disability” elaborates on this.

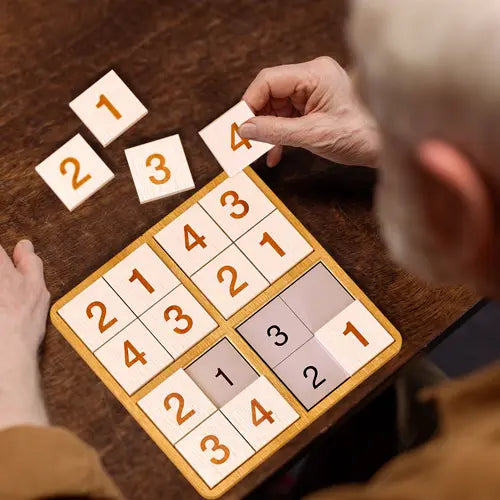

The Montessori principle of Independence guides us to always try to provide encouragement, cueing (signs, prompts) and other means of support to allow the person with dementia to continue to do tasks on their own for as long as they are able, even if it takes them longer. They don’t have to do the task completely or correctly, the important thing is that they are given the opportunity to participate regardless of the results. They must be given the time to do it with the least amount of prompting necessary to prevent them getting frustrated.