You may have heard the term "excess disability". What does it mean? Excess disability refers to the loss of an ability that comes from something other than the disease or impairment itself. In dementia care, this generally refers to the loss of abilities that go beyond the physiological changes that are caused by the dementia.

In other words the dementia disease didn't cause the loss, something else did. For example, the client's caregiver may have taken over the job of buttering the toast in an attempt to be helpful and speed things up. This can result in the memory care client losing the ability to do the job at all. Even though they are still capable of buttering the toast (albeit slowly), they may no longer be able to recall the steps involved because they are no longer using those steps. There is no physiological reason for the loss, it is caused by lack of practice. This is an excess disability.

Excess Disability is the loss of ability caused by something other than the disease or impairment itself. In dementia, this normally refers to the loss of ability through lack of use.

Because there is no underlying physiological reason for the loss, the ability can often be regained by helping the person access those forgotten steps in their procedural memory. You may have seen this happen with some of your clients - you've worked with them and they surprise you by doing better than they've done in the past. It is much more difficult to regain the ability than it is to retain it in the first place and that is why it is so important to maintain function as long as possible.

This will not only help the person retain their self-esteem and confidence, it will also minimize the assistance that they will require as time goes on. As frustrating as it may be to watch as the person struggles through the steps involved in doing a simple task, they should be allowed to do it. Not only does this help prevent excess disability, it also provides you with the opportunity to share in the satisfaction as the person successfully completes the task.

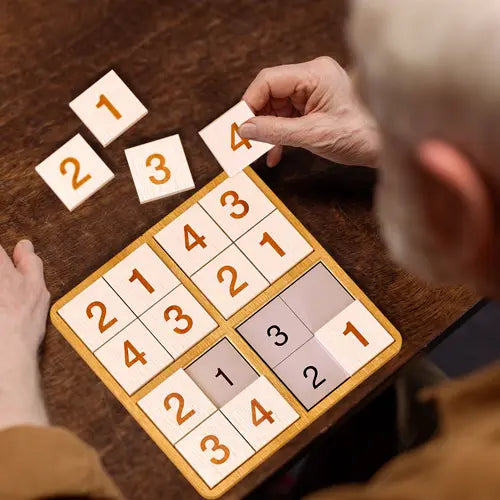

If you look around at dementia patients, you probably can identify different abilities within the group. One person may be able to the shuffle cards at the Crazy Eights game, another may be able to separate the whites from the yolks in a baking group, someone else may be able to use a computer. These are abilities that should be encouraged and retained.

Rather than speed the card game along by shuffling the deck and dealing for them, support the person who can do it for themselves. Offer them the deck and provide the guidance that they need to accomplish it successfully. As their ability naturally declines as the de mentia progresses, do what you can to ensure that they can still shuffle and deal. Use bigger cards, make sure that they are not slippery or sticky, write down the steps involved if that will help. If it comes to the point where they can no longer shuffle, encourage them to use the automatic shuffler and then deal. The idea is to keep the person doing what they can for as long as possible. It takes more time and more planning and work on your part, but the person will take pride in their accomplishment and this will positively impact other areas.

Another way that you can help people with dementia retain some ability to do things for themselves and help prevent excess disability is through the use of appropriate signage. Labeling the coffee mug cupboard, for example, may allow someone to get their own cup of coffee where otherwise they may need assistance. Labeling the clothing drawers may help them to be able to dress themselves. Signs, labels and other visual supports are known as "environmental cues".

Signage can also be used to give the person the support they need to find their way around, helping them retain a sense of independence. Their ability to do this is known as "wayfinding".

It is not enough to simply post a written sign above a door and expect positive results. Helping with wayfinding involves a careful look at the routes that are normally followed, decision points that occur in those routes and establishing appropriate cues and signage to aid the person with dementia in finding their way. Signs may consist of written words, direction symbols (arrows, etc) and pictures. For example, if there are two separate wings that share a common dining room, a different colored line painted on the floor or wall for each wing would help people find their way back and forth. This is a simplification of what would be involved but it is representative of the concept.

In a similar way, written instructions can be used to assist people with dementia in retaining their ability to perform complex tasks. An instruction sheet on the use of the television remote control, for example, may allow someone to use the television on their own without assistance. Written instructions can also be used to help people with dementia with their activities of daily living such as brushing their teeth or getting dressed. The instructions should break down the activity into the necessary steps based on the particular person's needs.

This article touches on many key concepts of the Montessori way for people with Alzheimer's and dementia.